A taxidermied penguin-looking seabird at the Cincinnati Museum Center was the last of its kind in the world. That finding was confirmed by scientists in Europe and New Zealand and published recently in The Linnean Society of London.

The stuffed great auk has been at the Cincinnati Museum Center since 1974, but it took researchers combing through a trail of ancient DNA, letters, photographs and auction records to make the connection.

"Recently, we discovered that it is the last female that was ever captured in the wild," says Heather L. Farrington, Ph.D., curator of zoology at the museum. "It was actually a mating pair, a male and a female that were captured on an island called Eldey Rock off the coast of Iceland, and the male was found in a previous scientific study, but the female was not."

The discovery of the lone male specimen set off a worldwide hunt for the female. The Cincinnati Museum Center knew the story of its specimen, but it didn't realize it was so special.

In the 19th century, great auks were highly prized for their meat, fatty oils, and feathers. The birds were hunted into extinction, with the last two coming from an island in Iceland.

"It was known that there were two more on Eldey Rock, and some folks went out and caught them, killed them, and sold the carcasses on the mainland," says Farrington. The nesting pair's egg was smashed.

The birds were taxidermied, but some of their soft tissue was preserved in alcohol. The specimens then changed hands numerous times, and the tissue ended up in the fluid collections of the Natural History Museum of Denmark. That's how scientists were able to make the identification.

They dug through historical sale and auction records and personal correspondence to identify five possibilities to test from a field of more than 80 known remaining great auk skins held in collections worldwide.

The male was identified in 2017 in the collections of the Institut Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique in Brussels, Belgium, known as the ‘Brussels Auk.’

The female remained a mystery.

Now, 180 years after the birds' deaths, more digging through photographs, letters, and auction records led to discovering the female's remains are in Cincinnati.

"We were able to generate genetic profiles from that soft tissue and then try to match it with taxidermy skins from all over, different collections, different museums and whatnot. So because of that soft tissue being in a museum and having it documented as coming from these last two great auks, that's the only reason that we could verify that ours was from the last collection," Farrington explains.

Cincinnati's great auk came about after a museum benefactor took a trip to Europe in the 1970s.

"A donor from the museum was traveling in England, and there were great auk specimens up for auction at an auction house in London," Farrington says. "They contacted the museum and said, 'Hey, they have some great auks for auction here in London. Do you guys want this?' And we had a very, very generous donor purchase those for us on behalf of the museum, and brought it back, and it's been in our collection ever since."

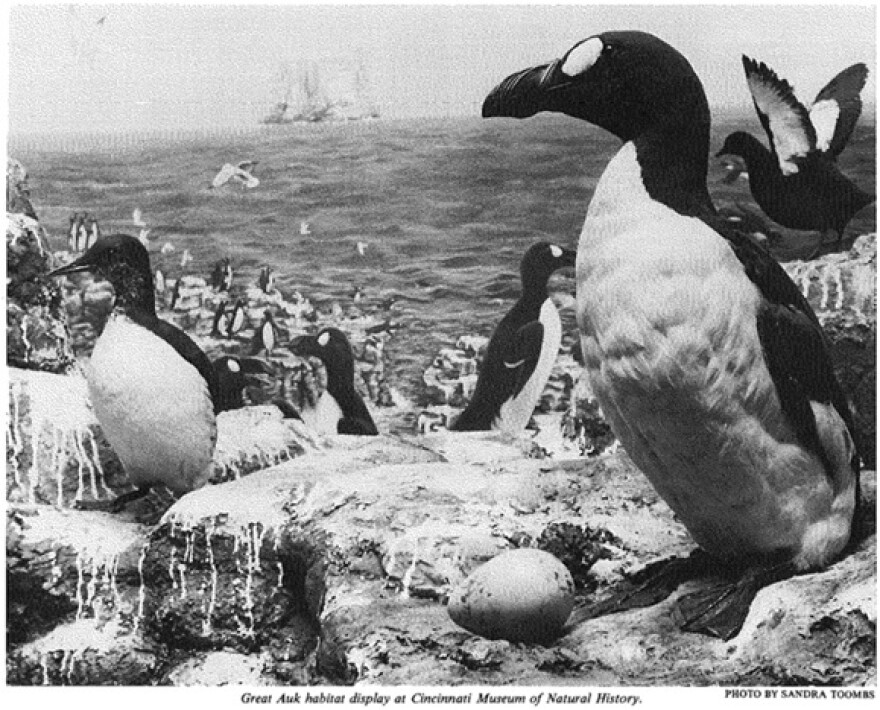

Farrington says while the great auk is flightless and looks a lot like a penguin, it isn't one. It's most closely related to a group of seabirds called razorbills.

The discovery continues an odd connection between Cincinnati and extinct birds. Martha, the last passenger pigeon, died at the Cincinnati Zoo in 1914. Four years later in 1918, Incas, the last Carolina parakeet died at the zoo as well. Coincidentally, Zoo Director Thane Maynard confirms Incas died in the same cage where Martha had died four years earlier.

Martha was sent to the Smithsonian. Incas was also promised to the Smithsonian, but news reports suggest the bird never showed up there.

As for Cincinnati's great auk, Farrington says, "it's pretty amazing to know that it is the last one, and it'll stay here in the collections at the museum center."

Read more: