This story is part of the Curious Cbus project. You ask the questions, and WOSU investigates to get the answers. R. Webb asked, "What happened to Columbus's trolley cars?" and Anonymous asked, "When were the electric cars totally discontinued? Where did they run?"

For a moment in 2008, it looked like Columbus might see itself with streetcars once again.

Then-mayor Michael B. Coleman had brought his proposal for a modern streetcar system all the way from a State of the City address in 2006 to the desks of City Council. By the time Coleman requested approval for funding, the decided plan would be 2.8 miles along High Street, running from downtown to Ohio State.

The cost? About $103 million to start things up and $4.5 million per year to keep it rolling.

Such a system, consultants found, would generate tens of millions of dollars in economic benefits, generating new jobs and revitalizing the city’s downtown.

It never happened. Ten years since it was proposed, any type of streetcar system is still notably absent from Columbus. Any plans to revive the idea have been shelved, or are being put together under-the-radar.

When did things go off the rails? To answer that, we went all the way to the beginning.

A Long Commute

Back in the day, Columbus, once known as “Arch City,” was not just famous for its extensive streetcar system. It was actually designed and expanded around it.

Streetcars first arrived in Columbus in 1863. Those ones weren’t powered by electricity, of course, but by horses.

And according to Alex Campbell, who runs the historical website Columbus Railroads, those first cars weren’t particularly efficient.

“They go about 4-5 miles an hour,” he says. “It was pretty slow and tedious.”

But they cost just a nickel, and all of a sudden, people who didn’t own their own horses had greater flexibility in their work and home lives. Remember: Shop owners and other business people tended to live above or at least in walking distance of their jobs. Only the wealthy could afford to commute.

As in other cities, horsecars changed everyday city life – a shift that would only quicken when electric streetcars came in – and ushered in the development of the suburbs.

“Now a person of even modest means could live somewhere other than a block or two from where he or she worked,” wrote Ed Lentz in Columbus: The Story of a City. “A working person could live away from the noise, smoke, and dirt of the downtown factories and in a neighborhood with trees and grass like more prosperous people were wont to do.”

The first horsecar line ran a mile and a half, south from the Columbus Union Depot on High Street. Over the next 29 years, horsecar routes expanded to a total of 34.5 miles around the city – while Columbus’s population expanded from 18,000 people to 90,000.

Streetcars were not public works projects, Campbell emphasizes. Rather, they were a for-profit business. In the late 19th century, two companies still operated: The Columbus Consolidated Street Railway Company dominated, and the Glenwood & Green Lawn Railroad Company ran additional lines.

By the end of the 1880s, though, the horsecars were ready for an upgrade.

Technological advances had allowed for a much faster and sustainable alternative – and besides, Campbell says, “the horses were dumping in the street, so they were dirty and smelly.”

“It was just such an improvement to go to electric.”

“Something of a Fairyland”

Electric streetcars in Columbus got a very short test run in 1888, with an experimental line running just a half mile to the State Fairgrounds.

Just two years later, the streetcar companies began electrifying all their vehicles. A wire overhead would provide the positive charge, and a rail below – on the street – would provide the negative.

One motorman would operate the car, and a conductor would collect fees. Not only were the cars faster, at about 14 miles an hour, but they could be heated in the winter.

When the process of replacing all the horsecars finished in 1892, the two companies consolidated into one, and then combined with the electric light business. The Columbus Railway, Power & Light Company, as it was known by 1904, did more than build the streetcars themselves – it also built and maintained the infrastructure that powered them.

Lentz, in an article for This Week News, provides a glimpse at Columbus at the turn of the century:

“Marching through the middle of downtown was a long series of street-spanning metal arches,” he writes. “Impressive enough in the daytime, at night they were lighted and transformed the city -- especially right after a spring rain -- into something of a fairyland.”

Those arches, built in 1896, carried the electricity for the streetcars below. Although they only stayed up for around two decades, switched out for better forms of street lighting, their contemporary recreations serve as neighborhood markers up and down High Street.

Quickly, though, the streetcar company found itself with a problem. Even though everyone commuted to and from work on their lines, one Columbus Neighborhoods episode found, the streetcars were practically empty during the day.

The solution? Amusement parks.

Olentangy Park in Clintonville, which opened in the early 1890s, was bought by CRP&L to provide a destination for people in their leisure hours, near the end of the streetcar line. Indianola Park in the University District and Minerva Park in the Northeast opened around the same time for much the same purpose, according to a Dispatch article from 2012.

At one point the largest amusement park in the country, Olentangy offered up roller coasters, rides, zoo animals, a theater, a casino, and a lake house by the river. At Indianola, visitors could go to the swimming pool (necessary during the hot summers of the early ‘30s) and dance pavilion.

The parks all closed by the second World War, with the Depression severely cutting how much people would spend on entertainment. Olentangy Park eventually was converted to Olentangy Village, an apartment community. Indianola became a shopping center, and then a church.

It was nearing the end of the line for the streetcars, as well. When streetcars and interurban railways reached their heyday in the 1920s, Robert Vitale recalls in the Dispatch, “more than 700 miles of tracks crisscrossed the region.” A local ride still cost a nickel.

End of the Line

By the 1930s, Columbus had almost tripled in population since the start of electric streetcars. Nearing 300,000 people, the city required again a transportation overhaul to support its growing workforce.

The problem for streetcars were the rails. Extending and modernizing the lines was an expensive project. Not to mention, the streetcar companies were responsible for maintaining the street itself one foot outside the rail, costing them even more money.

So, they got rid of the rails. In 1933, the conversion to trolley coaches (which used overhead electric lines but no rails) and buses (which used neither) began.

“Buses were considered modern and mobile,” Vitale writes. “Streetcars were limited to the rails that carried them.”

The last true streetcar finished its route on Sept. 5, 1948.

Meanwhile, to reach to the outer limits of the city and beyond, gas-powered buses left the overhead lines behind entirely. And eventually, diesel just took over.

“In 1965 they got rid of the trolley coaches and then they could arrange the routes any way they wanted to,” Campbell says. “It was so much more flexible, and they could lay their bus line out where the customers were.”

Not to mention, Campbell says, people liked the fact that without the overhead wires, they could look up from the street and see the sky.

That year, the bus system – still privately run by The Columbus and Southern Ohio Electric Company, a success to CRP&L – began fully serving a city of around 500,000 people.

An Attempted Revival

During his 2006 State of the City speech, then-mayor Michael B. Coleman announced his grand plan: The city, along with some businesses, would spend a quarter of a million dollars looking into how to bring streetcars back to Columbus.

One of the big inspirations was the Portland Streetcar in Oregon. That city at the time had 10 modern cars in its fleet, making 42 stops throughout the city. Little Rock, Arkansas, and Memphis, Tennessee, also had promising-looking options of their own.

Coleman convened a Downtown Streetcar Project Working Group to see if people even wanted streetcars or trolleys, and commissioned the Danter Company to compile a report to look at the potential cost and economic impact of such a system.

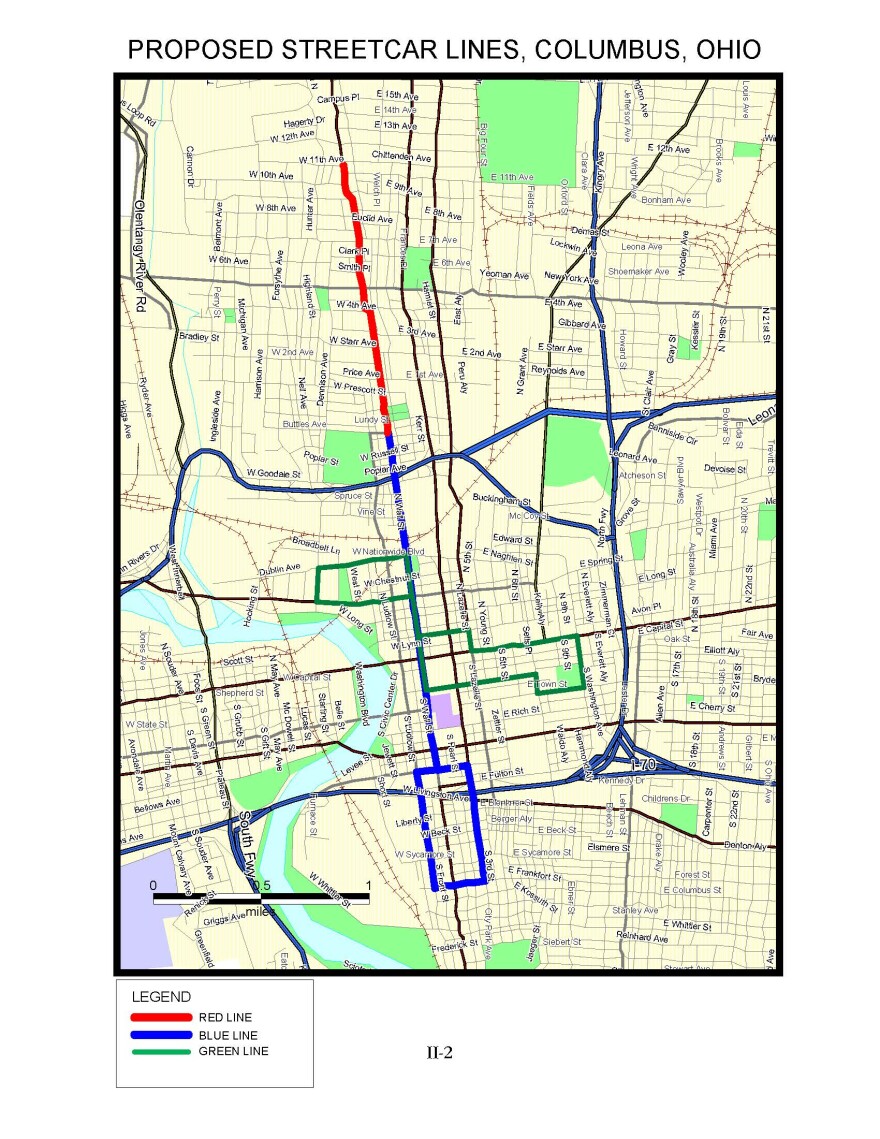

By the end of the year, the 42-member working group presented its findings to City Council. Three different routes for a streetcar circulator were suggested: a 2.1-mile route on High Street from German Village to the Short North, a 1.3-mile extension up High to the south end of Ohio State University, and a 1.1-mile line looping around the Arena District.

Overwhelmingly, people opted for the High Street route, which was also the most affordable option at an estimated cost of $64-77 million. Plans were starting to come together.

Marc Conte, a board member of Transit Columbus and an original member of the streetcar working group, says they got pretty far in the process.

"But the real question was, where would the capital and operating costs come from?”

The expenses came from a number of places: the tracks themselves, building the overhead electrical system and buying the streetcars, which would be modern like in Portland. But adding streetcars would also necessitate improvements to the roads and changing light signals. And keeping up the system year after year would also be expensive.

The government started looking into additional taxes as well as charges to private businesses.

“But that’s when the recession hit,” Conte says.

The market crashes in 2007 put a sudden stop to the plans. Columbus found itself with a severely shrunken budget, and already had to ask voters to increase the income tax.

“The city really needed to focus on making sure they could provide the basic services: safety, trash pickup, all the other stuff,” Conte says.

Understandably, streetcars got tossed aside.

Coleman didn’t give up, though. In 2008, he and the city hoped to benefit from President Obama’s stimulus plan. But state funding wasn’t coming through, and neither did federal money.

By then, the plan had changed. A 2.8-mile High Street route, extending from downtown to Ohio State, would cost about $103 million. The University would chip in some money, $12.5 million over 25 years, but City Council had to approve the rest. A 4 percent surcharge on hotel rooms, parking spaces, entertainment and sporting events, and restaurant tabs within the “benefit zone” of the proposed route would pay for much of it.

City Council, faced with its own deficit, balked. And by 2011, even the mayor had given up.

"The streetcar plan is not something the mayor is pursuing in any way," spokesman Dan Williamson said to the Dispatch.

The right thing at the right time?

Columbus may have let go of streetcars, but some of its residents are still holding on.

Columbus Underground announced this year that Mayor Andrew Ginther had returned to the High Street proposal with a new funding source in mind: Kickstarter.

Of course, that was just an April Fools prank. (At the $1,000,000 donation level, you get naming rights to the streetcar – as long as the name isn’t Trainy McTrainface.) But they aren’t the only ones with perhaps a little bit of resentment.

When Columbus announced as the recipient of a federal Smart City grant from the Department of Transportation, to the tune of $40 million, neither streetcars nor light rail were part of its proposal. Grist and Transit Columbus, among other organizations, took issue with the city’s emphasis on autonomous cars and belief in “leap-frogging” light rail entirely.

After all, Columbus is still the largest city in the country with no rail service whatsoever - even Cincinnati got its own streetcar system, the Bell Connector, this year.

For what it’s worth, even the streetcar historian isn’t optimistic about reviving them. Though Campbell says he thought some of the proposed route worthwhile, he’s not convinced the plans were ever economically realistic.

“If you’re going to say, ‘Okay, that streetcar has to pay for itself by the riders,’ forget it, that’s not going to work,” Campbell says. “And that’s true of any passenger transportation. It doesn’t pay for itself.”

Conte, as well, says Transit Columbus has moved on from the old plans – in large part because the city doesn’t seem to need it anymore.

In the years since the High Street circulator was proposed, COTA introduced a free, bus version of essentially the same route: CBUS, which goes from the Brewery District, through downtown, and into the Short North. If the goal is helping development, a streetcar would need to find a different area to service.

“In the case of where the circulator is running, I’m not sure if you need much encouragement,” Conte says, suggesting the Discovery District instead.

Who knows where the city will be by the time a streetcar started running? By 2050, the Mid-Ohio Regional Planning Commission estimates the region will add an additional million people. Whatever transportation systems Columbus invests in can’t be built for the city of yesterday.

Franklin Conaway, a consultant with the Columbus Street Railway Company – a nonprofit advocacy organization that formed in 2011 – insists the idea is not dead yet.

“There are still people and organizations in Columbus who believe that a modern streetcar system is the right thing for this city at this time,” Conaway said.

Streetcars, after all, helped Columbus become a modern city once.

Have a question about Columbus, the region, or the people of Central Ohio? Submit it to Curious Cbus and WOSU will work to find the answers.